Overview

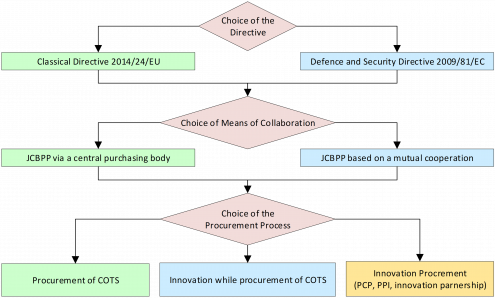

In a collaboration with a CPB, the regulation of the Classical Directive might force CAs to prefer types of collaboration where the procurement procedure is conducted entirely by the CPB – a scenario most suited for COTS, but also where the desired innovation is achieved by giving a novel use to an otherwise non-innovative product.

In case of innovation procurement, collaboration agreements must be sufficiently flexible in order to accommodate the possibly changing scenarios in the course of the product development and rise of unforeseen circumstances.

Establish a timescale and agreeing on the organization of the three phases of procurement, specially to the preparatory phase.

Within the preparatory phase, CAs must pay attention, during the technical dialogue, to the need to refrain from engaging economic operators to an extent that might later cause these operators to be excluded from the procurement.

Some EU funded projects

CLOSEYE: The main aim of this project was to pursue the validation of innovative services applicable to the surveillance of the EU Maritime Borders in real operational environment. More information can be found on the following web-page

https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/313184

EWISA: The project aimed at providing assessment of the management of illegal migration flows in the land border, through the increase of knowledge degree of operational situation and the enhancement of reaction capacity of the participating authorities responsible for land border security. More information can be found on the following web-page:

https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/608385

EUCISE2020: The project aimed at achieving the pre-operational information sharing on sea-basins between the maritime authorities of the involved European States. More information can be found on the following web-page:

http://www.eucise2020.eu/

BROADWAY: The project (still ongoing) aims at enabling a pan-European broadband mobile system for PPDR, validated by sustainable test and evaluation capabilities. More information can be found on the following web-page:

https://www.broadway-info.eu/

SHUTTLE: The project (still ongoing) aims at developing a toolkit which will facilitate the analysis of microtraces collected in crime scenes. More information can be found on the following web-page:

https://www.shuttle-pcp.eu/

JCBPP in the security sector: where to start?

Considering the level of compromise and the effort needed to develop a JCBPP, it is reasonable to analyse at least 3 phases:

Pre-tender phase, in order to test solutions regarding:

- International representation competences & authorizations needed for Collaboration agreement

- Internal budgetary regulations

- Public interest sharing and joint unmet needs decision

- Conducting joint preliminary market consultations:

- can be described as a formalised dialogue between the CA and other entities (economic operators, suppliers or independent experts), aiming to obtain answers to the question of how the problems of the CA can be solved, or

- Art 40 Dir 2014/24/EU states that “in view of preparing the procurement and informing economic operators of their procurement plans and requirements”, CAs may, for example, seek or accept advice from independent experts or authorities or from market participants, that can may be used in the planning and conduct of the procurement procedure, provided that such advice does not have the effect of distorting competition and does not result in a violation of the principles of non-discrimination and transparency.

For further information regarding benefits for CAs and suppliers, how to conduct a PMC, steps and appropriate measures, please consult ![]() How to conduct a PMC

How to conduct a PMC

Tender phase:

- The terms of procurement procedure and documents confirm to the Collaboration Agreement

- Procurement procedures are mostly conducted by one authority, a lead buyer

- When several collaborators decide to actively participate in a procedure, they must pay attention to the rules of collaboration as established in the Collaboration Agreement, in particular in unforeseeable situations or major developments during a negotiated procedure

- Law applicable to procurement procedure & to contract performance, as well as national practices should receive advance attention

- Collaborators in a JCBPP should acknowledge the fact that national variations interpreting the scopes of the Classical Directive and the Defence Directive are possible

- Awarding criteria definition

- Members of the competition jury

- Competence regarding contract monitoring and application of penalties

- In innovation procurement, what are the criteria for sharing risks? And how to manage “joint” IPR? How to avoid shifting too much (unreasonable) risk to the contractor?

- It is necessary to distinguish between the acquisition of IP rights from purchasing products in which IP is embodied

- Traditionally, IP is divided into three mais categories: (i) copyright, (ii) related rights, and (iii) industrial property, being trade secrets a sub-category of the latter (Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property)

- The allocation of ownership in IP is a key issue for fostering innovation (Commission Notice – Guidance on Innovation Procurement. Brussels, 18.6.2012. C(2021) 4320 final. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/45975 )

- It is important that public buyers define upfront, in the tender documents, the allocation of IPR linked to the public contract, paying attention to:

- Transfer all the IPR attached to a purchase to a contracting authority may stifle innovation because without IPR, the contractors may be prevented from re-using or even adapting/improving the innovation, possibly resulting in lower quality and higher costs for the contracting authority

- To boost economy and foster innovation, the EC advises Member States to consider leaving IP ownership to the contractors when appropriate, unless there are overriding public interests at stake or incompatible licensing strategies in place, e.g.:

- Significant difference between purchase and licensing relates to the stability of the right to use IP. On one hand, if CA acquires an IP license, there are risks that the right to use the IP could be lost; but on the other hand, IP ownership allows it wider use compared to license, but obliges the CA not to hinder innovation, i.e., not to block the use of IP by other entities

- The owner of IPR has an obligation to maintain IP and enforce IPR. It cannot be said that licensing or purchasing is better than other because it all depends of the procurer’s objectives.

- It is necessary to define clear IP clauses in the tender documents for all public procurement procedures

- The allocation of IPR must ensure that the procurement takes into account the applicable IPR legal framework in Europe and at national level

- Many international legal instruments define IP as human rights, namely, moral rights, which have more relevance in procuring copyright-protected works

Performance/Pos-Tender Phase

- Contract performance and assessment results

- Did the contractor release what was contracted?

- Did we contracted what we needed?

- If applicable, what happened?

- What must be changed in a future JCBPP?

- The contract performance stage begins when the contract enters into force

- Questions as entering into force, application of penalties, modification, subcontracting or termination need are particularly relevant in contracts for innovation

- Contracts needs extra flexibility and are subject to significant changes

- In more complex tasks and innovative contracts, the need to prematurely exit the contract without penalties can be essential for contracting parties: in this case, the structure of an innovation partnership should be considered

JCBPP and IP in the Security Sector

JCBPP and IP in the Security Sector

Joint Cross-Border Public Procurement (JCBPP)

Innovation Procurement (IP)

How to: Guide for JCBPP & IP

Ethics in procurement